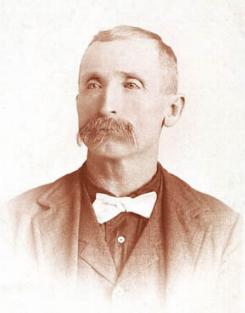

Corporal Charles Fosdick

Fifth Iowa Volunteer Infantry

Charles Fosdick, a 19-year-old Iowa farm hand, heard and answered the call to serve the Union "when my heart beat with a patriotic impulse." Out of Allamakee County, he enlisted for a term of three years in the Fifth Iowa Volunteer Infantry, Company K, on July 15, 1861 at Burlington, Iowa. Like many other families who enlisted together, his 21-year-old brother, John, joined him in the same company.

Charles' participation in the regiment's engagements included the capture of Island No. 10, the battles of New Madrid, Iuka, Corinth, and Champion's Hill. At Champion's Hill, Charles helped critically wounded brother off the battlefield. After the battle and siege of Vicksburg, he received his promotion to Fifth Corporal on July 27, 1863.

As a member of the color guard during the battle of Missionary Ridge (on Tunnel Hill) at Chattanooga, Tennessee, November 25, 1863, he and about ninety other members of the Fifth Iowa were taken prisoner. He narrowly escaped death as he and some of his companions were swept into the Rebel entrenchments atop the hill. Three men died at his side, but fortunately the bayonet thrust at him penetrated only his clothing and belt.

With only the clothing on his back, Fosdick and fellow enlisted members of the Fifth were imprisoned through the bitter winter of 1863-1864 on Belle Isle at Richmond, Virginia.

In early March, Fosdick and a detachment of prisoners were crowded into boxcars for a long ride deep into Georgia, to their next place of imprisonment, the newly constructed Camp Sumter, better known as Andersonville. Here he survived great deprivation for the next seven months.

Once, near death in mid-summer, his skeletal body ravaged by scurvy, two of his cousins, recently captured during the Battle of Atlanta, saved his life. They located him after a two-week search in this sea of suffering humanity. One sold his gum blanket for three greenback dollars, buying a three-pound can of potatoes for the dying man. They buried these in the sand where Charles slept. Eating them morning, noon and night helped keep the disease in check and helped him pull through his brush with death. Charles wrote that his cousins cared for him "with wife-like tenderness, and one or both stayed by my side almost continually, and spoke nothing but words of encouragement."

It was a huge blow to him when his cousins left the stockade on September tenth in a special prisoner exchange. Another emotional setback occurred three days later, when the last surviving member of his company died, leaving him alone. But he turned this tragedy to a positive end when he determined: "I nerved up for the worst and resolved to see the thing through, that I might tell the poor boys' friends where they died." Around this time, detachments of prisoners were being relocated to other prisons, with the first detachments in, being the first out. He was among the first to arrive, but only those who could walk out on their own were allowed to transfer; Charles was not among that lucky lot, being still crippled with scurvy. Only 1,200 men remained in the now desolate, fetid stockade, in a space recently occupied by more than 30,000 desperate prisoners. Once again, he put his mind to the task of walking out. He succeeded, and when the final group exited the camp in October, Charles was on his feet, aided by an old tent pole.

His next stop was the prison at Florence, South Carolina. Here a heart-rending accident occurred. While passing under the only remaining tree in the stockade, a limb cut by another prisoner atop the scraggy pine, came crashing down upon him, striking his shoulder, partially dislocating his neck and breaking bones. Near death for two weeks, comrades helped him somehow pull through, although the injury plagued him for the rest of his life. At the war's end, upon his release from confinement he was fitted out with a new uniform which he said "hung on me as gracefully as a shirt on a beanpole." A man small in stature to begin with, during his confinement he lost forty-nine pounds, weighing only sixty-six pounds when he was liberated. He was officially mustered out of the service April 18, 1865.

After the war, Charles resumed farming in a limited capacity, due to his Florence injury, which caused blackouts from five to twenty-five times a day. In 1887, he wrote a book chronicling his days as a Civil War prisoner of war, entitled 500 Days In Rebel Prisons. He died at his home in Blythedale, Missouri, on May 17, 1913.

This detailed account of the life of Charles Fosdick is provided by his great-great-grandson, John Walker.

Return to the Fifth Iowa Infantry Personnel

Return to the History of the Fifth Iowa Infantry