Civil War Prisons

Andersonville, Georgia +++ Elmira, New York

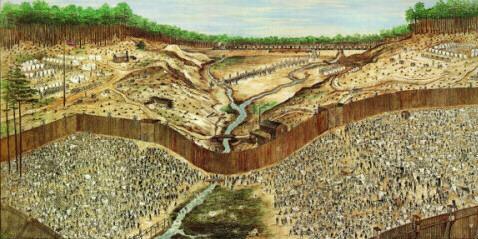

As daunting as combat was, an even more fearsome specter for some was the possibility of capture and internment in a prison camp. A number of veterans of the Fifth Iowa Volunteer Cavalry were captured in various engagements throughout the war. The picture above is comes from a drawing of the notorious Camp Sumter (better known as Andersonville Prison) where some of them were incarcerated.

The stockade at Andersonville was designed to hold a far smaller number of prisoners that it eventually contained. Part of this responsibility lies directly with the United States government, and its representative, General Ulysses S. Grant. During most of the war, formal prisoner-exchanges had been conducted. Tragically, the Union eventually determined for strategic rather than humane reasons that since their manpower resources dwarfed those of the Confederacy, it was preferable to maintain in captivity the southerners they captured, while allowing their own men to languish in southern prisons.

The magnitude of this tragedy is nowhere clearer than in the example of Andersonville, where meager Confederate resources were stretched far beyond their capacities. Nearly 50,000 Union prisoners were detained at Camp Sumter during 1864 and 1865. Of these, more than 13,700 perished due to illness. Inadequate food, combined with the filth of the camp made the men vulnerable to epidemics of dysentery and scurvy. The simple fact is that the Confederacy did not have the resources to adequately maintain and provide for the huge numbers of Union prisoners.

At the war's close, only a single military commander was tried for war crimes. In 1865, Camp Sumter's superintendent, Major Henry Wirz, was convicted and sentenced to be hung by a United States military court. Some argue that he was a scapegoat for national outrage. Others argue persuasively that if Wirz was guilty of crimes against humanity, his northern counterparts were not innocent themselves.

The strongest case for northern atrocities against prisoners is found in the case of the prison at Elmira, New York. One former prisoner wrote:

talk about Camp Chase, Rock Island, or any other prison as you please, but Elmira was nearer Hades than I thought any place could be made by human cruelty… Snow and ice several feet thick covered the place from December 6 to March, 1865. We were in shacks some seventy or eighty feet long, and they were very open, with but one blanket to the man. Our quarters were searched every day, and any extra blankets were taken from us. For the least infraction, we were sent to the guardhouse and made to wear a "barrel shirt" or were tied to by the thumbs for hours at a time. There was one Major Beal who, I believe, was the meanest man I ever knew. Our rations were very scant. About eight or nine in the morning we were furnished a small piece of salt pork or pickled beef each, and in the afternoon a small piece of bread and a tin plate of soup, with sometimes a little rice or Irish potato in the soup where the pork or beef had been boiled... After the surrender of General Lee, we thought it would be better, but were mistaken.Another former inmate of "Helmira," as it came to be known, wrote:

If there ever was a hell on Earth, Elmira Prison was that hell, but it was not a hot one, for the thermometer was often 40 degrees below zero. There were about six thousand Confederate prisoners, mostly from Georgia and the Carolinas... My weight fell from 180 to 160 in a month. We invented all kinds of traps and deadfalls to catch rats. Every day Northern ladies came in the prison, some followed by dogs or cats, which the boys would slip aside and choke to death. The ribs of a stewed dog were delicious, and a broiled rat was superb.

Believe it or not, the per capita death rates of Andersonville and Elmira were within a couple of percentage points of one another. That means that when a rebel soldier entered the gates of Elmira, he was just as likely to die of disease or the elements as a yankee trooper was when he entered Andersonville. And yet, in our history books we only hear one side of the story. Descendants of proud Union veterans who risked, and surrendered, their lives in a noble cause have reason to be ashamed at what transpired at Elmira. For there in New York, the prison officials had no excuse when it came to a shortage of supplies. And when Wirz stepped onto the gallows, it could be strongly argued that he should not have been alone. The horror of Elmira is that many of the conditions which caused the deaths were deliberately determined by the U.S. Commissary-General of Prisoners, Colonel William Hoffman. At one point, freezing prisoners had to watch as all of the non-gray clothing sent by relatives to relieve their suffering was piled into a mound and burned. Unbelievably, the Union surgeon at Elmira, Major F. L. Sanger is alleged to have once claimed that he was responsible for more Confederate deaths than any Union officer in the field. One prisoner who survived his "care" and later went on to become mayor of Richmond, Virginia, wrote:

The chief of the medical department was a club-footed little gentleman with… a snaky look in his eyes, named Major F. L. Sanger. He was simply a brute, as we found when we learned the whole truth about him from his own people. If he had not avoided court martial by resigning his position it is unlikely that even a military commission would have found it possible to screen his brutality to the sick.

War is violent and horrible. When people have been removed from combat, as have prisoners of war, continued violence is inexcusable. The picture below comes from the cemetery at Elmira, but its neat rows of tombstones look little different than those of Andersonville. In death there is a profound equality, and it is tragic that so many thousands of soldiers whose war should have ended when they laid down their arms never lived to return home to their families.

Still, there are two positive facts which deserve mention in this admittedly superficial discussion of a complex subject. The first is a comment from one of the Confederates quoted above, who mentioned something that reflects well on the descendents of "westerners," such as those who for the most part filled the ranks of the Fifth Iowa Cavalry. He wrote, "my experience was that when you met a Western man you met a gentleman or soldier; but when you met a 'down Easterner' or a Southern renegade, you meet the other fellow." On a more serious note, there was an amazing miracle which transpired at Andersonville. During the heat of summer when the polluted stream running through the camp was nearly dry, a spring erupted inside the camp. The prisoners recognized this as an act of God and named it Providence Spring. Its waters flow to this day.

In 1970, the United States Congress designated Andersonville a National Historic Site dedicated as a memorial to all the American prisoners of war. Thus, a century after their common misery, Andersonville came to seen as a monument to the courage and sacrifice of all imprisoned soldiers, sailors, marines (and eventually, airmen) regardless of the color of their uniform.