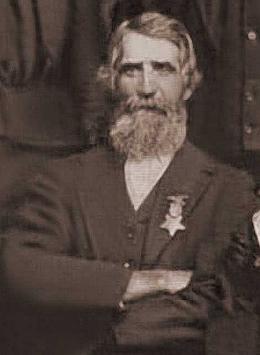

Private George Washington Husted

Fifth Iowa Volunteer Cavalry

George Washington Husted distinguished himself by service in two Iowa regiments. He was born September 16, 1835 in Greene County, New York. He set out for Ohio with family friends when he was fifteen years old. Husted remained in Ohio three years before moving on to Iowa. He was married in 1854 to Martha Sherlock and had a son in 1855. His wife died in 1856 leaving him and his son to carry on.

He enlisted at Marengo, Iowa in September, 1861 in Company G, Eighth Iowa Volunteer Infantry. They were taken to Davenport and St. Louis, then to Springfield, Missouri for a week. Their headquarters for the winter was in Sedalia, Missouri, but they were kept busy much of the time chasing rebels through that border state in an ongoing guerilla warfare.

The following spring, they were arrived Pittsburg Landing, participating in the battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862. There Husted's regiment was in the area called the Hornets Nest and a rebel bullet passed through his blouse--the nearest he ever came to being wounded. During the battle he was taken prisoner and was shipped by the Confederates to Macon, Georgia, where he was confined for six months and fourteen days. At first they had no shelter in the stockade, but after a couple of months, lumber was brought in and the prisoners built rough barracks. Rations were fair, and the hardships experienced at Andersonville and Libby, later in the war, were not in evidence.

Husted was among the prisoners who were exchanged that fall, and he returned to St. Louis. There he was discharged on account of disability-a chronic trouble with dysentery that had developed in prison. December of 1862 found him home in Marengo. There, with proper care, he improved and grew eager to return to the front.

In February of 1864 he reenlisted in Company B, Fifth Iowa Cavalry. The regiment rode throughout the South and participated in many skirmishes and raids. It was an exciting life. Sometimes they did not camp until midnight or later, after a full day in the saddle.

Leaving Decatur, Alabama on one raid, with three days rations, they pursued Confederate General Wheeler, and kept after him until they ran him against the Tennessee River, where they had a fight and several were killed. They were gone twenty-one days instead of three, tearing up railroads and burning depots and mills--terrible work, but a most necessary part of the campaign.

At Marietta, Georgia, they were placed under the command of Colonel McCook. "Pappy" Sherman was then shelling Atlanta, and the Fifth Iowa was dispatched to tear up a railroad leading to that city. Two troops were dismounted and were at work when the pickets reported that a Rebel force was advancing. The boys were ordered to remount and the retreat was led back by the same road which they had come. After proceeding some miles, however, they attempted to make a shortcut through the woods. Night arrived and it began to rain. The men became separated. Husted and a comrade entered a swamp but waded through and struck a road on the other side. By this time it was very late and the two of them lay down behind some brush not far from the road. Whether their snores or something else drew the attention of passersby and they were awakened at about three o'clock by a bunch of "Rebs" who ordered them to rise. They had no alternative but to surrender… and Husted became a Confederate prisoner for the second time.

A few miles from the scene of their capture they witnessed a skirmish between Sherman's rear guard and some Confederate cavalry, but were too closely guarded ti attenot ab escape. Then some of their clothes, including shoes and coats, were taken from them by the suffering Confederates and they were forced to march two miles to Newlen, Georgia barefoot. At Newlen they were locked in a cotton shed, where Husted managed to free some cotton from a bale to make a bed. They were also given hardtack to eat. That night more prisoners were brought, until in the morning there were three hundred men crammed into the shed. For several days they were shuffled from one place to another. They heard the incessant boom of Sherman's siege guns, and they knew he was hammering away at Atlanta. By and by they saw the rebel artillery come trundling by from Atlanta, and they knew the southern stronghold had fallen.

They were then taken hurriedly by train to Macon, Georgia, and then to Andersonville. Before being put into the stockade they were stripped to their shirts. Private Husted saw General Wirtz, the commandant of the prison, as they were entering. He was mounted on a large horse and Husted heard him command, "if you see anyone burying anything on the grounds, shoot him down."

At that time there were said to be 23,000 Yankee prisoners in the stockade. Six feet from the stockade was the "dead line," marked by posts with a strip on top. The man who so much as reached a hand past this line was instantly shot by a guard. Husted witnessed one man, occupied in getting water from the stream that ran through the stockade, reach up beyond the dead line in order to get some water that was not polluted; he was shot and killed before he could draw his hand back.

Once a day, around three o'clock, rations were provided, consisting of about half a cup full of beans, rice, or cornmeal. The beans were cooked in big gunnysacks and often contained sand, gravel and dirt.

Some Colored troops were also confined in the stockade. To show their contempt for the "Yanks," the Confederates gave the Negroes all the corn bread they could eat, but they were forbidden to share so much as a bite with the starving white prisoners. Each morning the dead would be carried out and buried by their former comrades, under guard. There were typically thirty to fifty every day. If a man died after this daily burial, he was left lying there until the next morning.

The prisoners, for a short time, were able to hoodwink their captors into issuing "dead men's ration," but they were soon discovered and each morning all the prisoners would be forced to gather on one side of the creek and march across in column of fours so they could be counted for rations. The Confederate officers were very impatient with this necessary delay.

Private Husted once told of his particular friend and bunkmate, Fitzgerald, who was baking corn cake one morning when they were called upon to assemble on the other side of the creek. When he delayed a little to finish baking that cake, a Rebel officer pulled out a revolver and shot at him twice, but did not hit him. The anger felt by Husted toward that officer for this act was scarcely controllable.

George was in this hole of infamy for nearly a month. From there he was taken to Charleston, South Carolina, for three weeks. There the Christian citizens, seeing the emaciated prisoners, would throw them baked chickens and other provisions across the guard line. This continued but a short time before the officers put a stop to it.

From Charleston, Husted was taken to Florence, Alabama, where he spent five months. Here there were eight thousand prisoners, and conditions were as bad as at Andersonville. The men were herded so close together that the vermin were the curse of their existence. Some of the stories Husted told about Florence may have been recounted here in connection with Andersonville. Conditions were sadly similar.

In the winter of 1864, Husted was paroled and taken to the hospital at Annapolis, Maryland. For eight weeks he was confined by fever, but at length, growing better, was given a furlough and returned to his Iowa home. When he got home he was again taken ill and his furlough was extended an additional thirty days.

After recuperating, Private Husted rejoined the Fifth Iowa at Camp Chase, Ohio. They spent additional time in the South and in August of 1865, they were discharged.

After the war, Husted went back to farming. He was married again in January, 1871. He and his new wife, Amanda Welch, raised eight children. Husted died on March 3, 1915 in Marengo, Iowa.

Most of the preceding material was taken from an interview George Washington Husted gave to the Marengo newspaper. Husted's proud great-great-grandson, John Langheim, provided this article for the Fifth Iowa Regimental Website.

Return to the Fifth Iowa Cavalry Personnel

Return to the History of the Fifth Iowa Cavalry